NON-LOOM TEXTILES

The first textiles fabricated by mankind were made by manipulating fibers with the fingers. It has been suggested that the craft of basketry was invented by primitive man and that the techniques developed were then applied to constructing other fabrics. A number of techniques were developed that involved looping, knotting, interlacing or twining strands together. The major difference between early baskets and textiles was not so much in the techniques but in the choice of materials. The more resilient and flexible a fiber used, the more supple the fabric constructed from it. Some of the methods that evolved are so effective that in parts of the world, such as central and eastern North America, the loom was never devised and even with the introduction of the true loom by colonists the techniques of working only with the fingers were not replaced.

PORTABILITY

WITH non-loom textiles the very fact that a bulky loom is not required, and that equipment is minimal means that work in progress is often portable and easy to pick up at any convenient moment. This is, of course, of prime importance to those who do not have a sedentary lifestyle or who are unable to devote prolonged periods to a single task. The supreme example of a portable technique is knitting, a craft that is practiced by men and women all over the world and is today one of the most common of all domestic textile crafts. On the Scottish islands of the Outer Hebrides there are still experts who are able to knit with one hand, while attending to their domestic chores, nursing the baby or stirring the supper, with the other. In the days of whaling and global exploration, sailors, away from home for months or even years at a stretch, spent a considerable amount of time knitting themselves articles of clothing or knotting lengths of twine into useful articles.

FRAMES

To maintain their structure and regular shape many textiles, such as crochet, only need to be held firmly by the fingers, but others need to be attached to a fixed point or stretched on some form of frame, as is necessary in sprang. These simple devices are rudimentary relatives of the loom.

WARP AND WEFT

MOST techniques that do not need a loom require only one set of elements — they are either weft-based like netting, knitting and crochet, or warp based like sprang, macramé and braiding.

NETTING, LINKING AND LOOPING

NET is a structure built up horizontally by connecting each row of weft to the previous one. The connection may be linked, knitted or looped, but has the appearance of being structured on the diagonal. All textiles made like this have a fair degree of elasticity.

Technique

THE foundation of most netted fabric is a horizontal thread or cord at either end to some sort of frame manageable length of yarn is then wound, onto a shuttle or bobbin and loose’ attached to the foundation cord in a serac of loops. On reaching the edge, the yarn worked back in the opposite directivity looping through the previous row and creating a new set of loops on to which the following row is attached. For a flexible structure the yarn is simply passed through the loops, but if a stronger fabric such as that required for fishing, is being manufactured then the yarn may be attached to the previous row with a suitable knot like a sheet bend. There are many variations on this basic principle. The density and strength of a looped or netted structure may be greatly reinforced by linking several rows together at the same time, introducing extra horizontal elements, crossing the yarn in a figure of eight or simply pulling the work tighter.

Uses

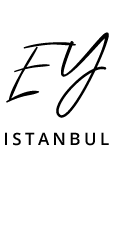

THE most obvious application of this technique is the manufacture of nets for fishing and storage or for use as hammocks. When the fibers or threads are worked tightly, strong, yet flexible, bags can be constructed. Such bags can be found all over the world, often incorporating fibers of several colors to build up decoration. Among the most interesting examples are the billows of New Guinea which are constructed in hourglass or figure-of-eight looping using a needle threaded with Pandanus fiber.

CROCHET

CHROCHET, which drives its name from the French for hook, is doubly interloped structure worked with a hook made of wood, metal, bone or plastic. As it is simple technique requiring only a hook and yarn, crochet work can easily be carried around and worked on at any convenient moment.

Technique

THE foundation of every piece of crochet is a chain. First a slip loop is tied and then a loop is pulled through this with the hook. A succession of loops are then worked through each other, one at a time, until the chain has reached the required length. To build a crocheted fabric subsequent rows are added by working a new sequence of loops, each one of which is hooked through the previous loop and also through the previous row. Variations on the basic stitch involve increasing the number of loops carried on the hook or linked together at the same time.

Uses

CROCHET, usually worked in wool, cotton or silk, lends itself easily to the making of open work, and such is the variety of stitches and their possible applications that the number of different articles that can be crocheted is almost limitless. As crochet is such a simple, but versatile, technique and work in progress is so easily transported, it has been adopted by the inhabitants of many lands and adapted to local materials and requirements.

KNITTING

KNITTING is the technique where an interlooped textile is created by horizontally manipulating a weft yarn with two or more needles. Traditionally wool is used, although sometimes cotton. The Egyptian Copts, a Christian sect who became famous for their skill, are credited with inventing the first true knitting. As Christianity spread, knitting spread with it, travelling as far as Peru with the Conquistadores in the 16th century. Although it originated in a hot climate, knitting is now most often practiced in temperate or cold countries and requires only an adequate supply of yarn. In Europe and Central Asia sheep or goat wool is used, but in the high Andes of Bolivia and Peru alpaca, Ilıma or Vicuna hair is more readily available and is knitted into beautifully soft garments. Plain, functional sweaters knitted with naturally oily wools are the choice of seafaring and fishing folk such as the inhabitants of Guernsey and the other Channel Island.

Technique

First row of stitches is cast on by looping the yarn onto one needle, pulling a second loop through the first with the other needle and picking the new loop up beside the first. A third loop is pulled through the second and so on until there are sufficient stitches for the required width. A second row is then knitted by pulling a new series of loops through the first, one stitch time. This is repeated until sufficient rows have been knitted to make one panel. When all the separate panels have been knitted, they are stitched together to make the final garment. It is possible to knit tubular items like socks and hats in one go, without seam, by using three or four needles.

The texture of the knit can be made more interesting by varying the stitch. For plain, or knit, stitch to loop of yarn is pulled through to the front, while for purl stitch it is pulled through to the back.

The most widely knitted fabric uses a stocking stitch which makes a smooth fabric comprised of alternate rows of plain and purl. When it is reversed, with the purl side as the face, it is called reserve stocking stitch.

Popularity

THE fact that knitting is simple to learn, needs no special equipment, other than a pair of needles, and is portable has ensured the survival of knitting as a domestic, as well as a commercial, textile craft. In any moment of leisure or when the hands are not required for other work, whether while watching sheep or watching television knitting can be done.

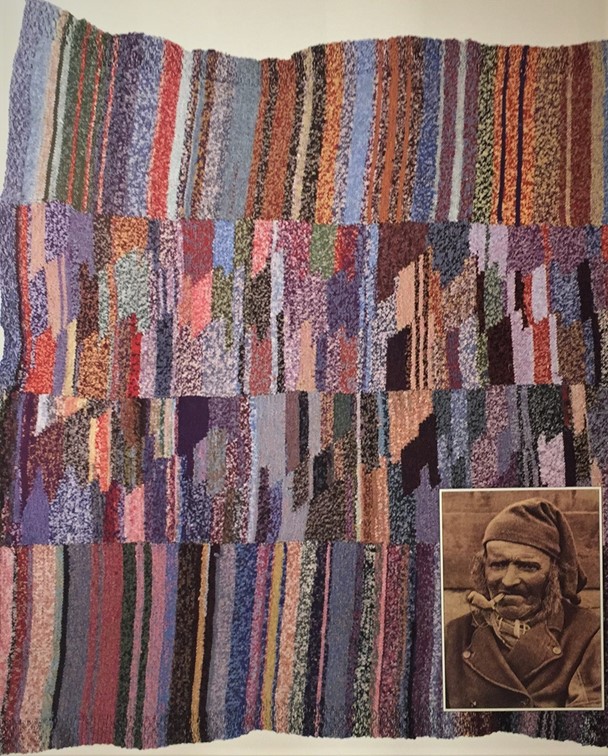

Scottish fisherman in a knitted hat.

TEXTURED KNITTING

The most famous textured knitting of all is Aran. Developed on the Irısh Aran Islands to protect fishermen from the hostile elements, Aran sweaters are knitted in natural white wool which does not detract from the bold, raised patterns of cables and bobbles. It is possible to buy imitations as far away as Kathmandu in Nepal.

Technique

CABLES imitate plaited or twisted rope. To achieve this effect one set of elements is slipped onto an extra needle and pulled over or under another set of elements to change the order in which the stitches are knitted. To emphasize the texture, the cable is worked in stocking stitch on a background of reverse stocking stitch. Using a cable needle, a number of different patterns can be created. Although textured patterns can be built up without the use of cable needles, by comparison they are dull and two dimensional.

Uses

FISHERMEN all around the coasts of Britain have relied for generations on warm, weatherproof pullovers, knitted for them by their womenfolk. Navy blue is the most typical color, but textured patterns on selected parts of the garment — neck, chest, sleeves or shoulders — were once a sure way of knowing whether a fisherman was from Whitby, Lowestoft or Guernsey. Sadly, these garments are now seldom made at home and plain, machine knitted jumpers have become the usual mode of dress.

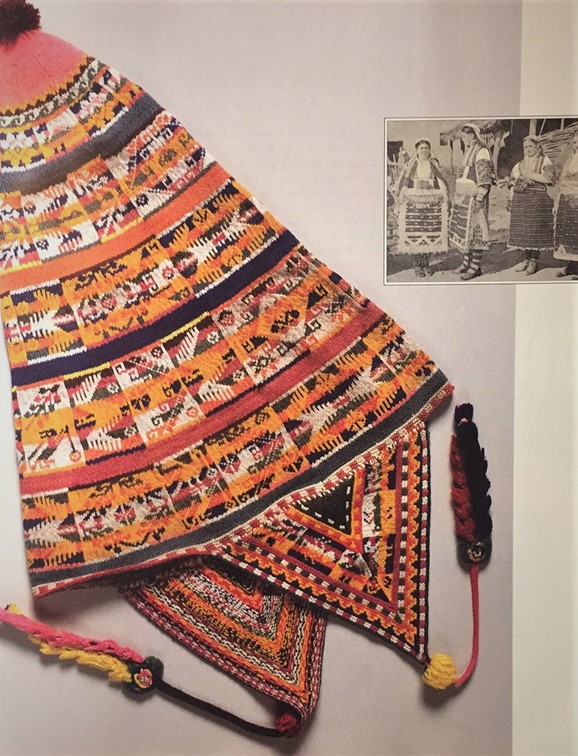

MULTI-COLOURED KNITTING

JUST as the introduction of dyed yarn increased the range of effects that could be achieved in weaving, so did many cultures build up a treasury of motifs and patterns in knitting. To this day men in the Andes record their marital and social status in the hats and belts they knit and the repertoire of designs used in the Scottish Shetland Islands includes motifs (such as the Armada cross) supposedly derived from the wrecks of ships from the dispersed Spanish Armada of 1588

In recent years knitting skills have been given a new lease of life amongst refugees, such as those from Afghanistan, who knit to their own designs using wool unraveled from garments given to them by aid organizations.

Technique

THE process of knitting in colour is very much like weaving with a supplementary weft, in that an extra color can float across the back of the knitting, surfacing when required to take over the pattern. It is possible to use several colors in a single row, but the more strands of yarn used, the harder they become to manipulate and the bulkier the fabric will be. Because knitting is a horizontal process it is easiest to build up patterns in bands or rows of repeated motifs. This can be observed all over the world from Fair Isle in Scotland to Afghanistan and from Norway to Bolivia.

Villagers in Western Macedonia wearing hand-knitted socks

BRAIDS

ALTHOUGH the word braid is often used to describe any narrow textile, irrespective of the method of construction, technically, a braid is a band manufactured by interworking a group of warp strands together diagonally across the width of the fabric. When carried out with a large number of strands, the interlacing bears a strong resemblance to a woven textile using both warp and weft. A technically more precise term is oblique interlacing.

The three-strand plait has been universally used, particularly by women, for keeping hair tidy, sometimes in quite complex styles as can be observed in West Africa. One of the most elaborate plaited coiffures is that used by Khampa women in Tibet who braid their hair into 108 plaits, a religiously significant number for Buddhists.

Technique

NUMBER of strands are suspended side by side from a foundation thread and each strand is interlaced diagonally to one edge, passing alternately over and under every other strand on the way. The strands originating on the left all travel to the right and all the strands on the right travel to the left. As each strand reaches the selvedge it changes direction and travels back across to the opposite side. In North America this is called double-band plaiting. In multiple-band plaiting a larger number of strands are used. These are divided into groups and from each group half the strands travel to the right and half to the left.

The introduction of coloured strands allows the creation of a variety of patterns which may be made more intricate by changing the direction in which selected strands are interlaced. Braids can be flat, tubular, solid and even three-dimensional.

Uses

A s the technique of plaiting or braiding lends itself best to the manufacture of narrow fabrics a few inches wide, it is most often used for making straps, belts and bags. Quite often plaits may be used to make fringes to secure the ends of larger textiles. The finest examples of textiles made With this technique are the Assumption sashes made by the Native Americans of the Great Lakes area. These are made of finely spun worsted wool with colorful repeated zigzag patterns.

SPRANG

SPRANG is an ancient method of making a stretch fabric. Although similar in appearance to netting, it is constructed using only warp without any added weft elements. Much used before the invention of knitting, the earliest archeological evidence of sprang is a hair-net made in around 1400 BC found in a Danish bog.

Technique

A SET of warp threads are always stretched between two beams or in a rectangular frame. A fabric can then be created by manipulating the warp threads, row by row, interlinking, interlacing or intertwining them. Small sticks may be set in to prevent the work in progress unravelling. Because the threads are fixed at top and bottom, any textile structure created at the top will also be created in mirror image at the bottom. If, after they have been worked, each row and the complementary row created at the bottom are beaten with a flat stick, forcing them to opposite ends of the warp, a compacted fabric will grow, one half growing from the top downwards, the other from the bottom upwards.

Eventually the two halves will grow until they almost meet in the middle. The unworked threads between them must be secured in place to prevent the whole structure unravelling. It is also possible to create two identical textiles by cutting the threads at this point.

Uses

ONCE used to make clothing, hats and gloves in many parts of the world, sprang is still in traditional use in Guatemala and Colombia for the making of bags and hammocks and in Pakistan for silk draw-strings for trousers. Now almost universally superseded by knitting, it has experienced something of a vogue •n the art-textile world as a medium decorative hangings.

MACRAME

MACRAME is a knotting technique used to make fringes, decorative braids and other articles. It is of ancient Near Eastern origin and reached Spain through the Moorish invasions (8th century onwards) and Italy through the Crusades (11th to 13th centuries). From Europe it was disseminated to other parts of the world largely by sailors. It came into popular vogue in the 19th century and has been in and out of fashion ever since.

Technique

MACRAME can be worked on a knotting board of cork or similar soft, but rigid, material on which the cords can be held in position. Every piece of macramé is started from a holding cord (see diagram opposite). The working threads are doubled and attached to the cord using double half hitches, or larks heads, and packed closely together across its width. As a guide to planning the work, the doubled threads need to be four times as long as the finished work. However, some knots or sinnets (several knots worked in succession to form a bar) are likely to take up even more thread so allowance must be made for this. On the other hand, an open knotted pattern will take up less thread.

The work proceeds downwards, joining sets of cords at intervals using a few basic knots and many variations, the main ones being the square knot, half hitch, double half hitch and the Josephine knot. Common variants include the picot, square knot sinnet, corkscrew sinnet and alternating square knots.

To finish off, loose ends can be knotted into tassels or worked into horizontal cording.

PLY-SPLITTING

PLY-SPLITTING work is one of the simplest forms of textile structure, a technique almost exclusively used in the manufacture of animal trappings. Cotton cord or sisal is sometimes employed, but the chosen material is most often goat hair.

Technique

IN Rajasthan in India a villager will spin out yarn from a bundle ofeither black or white goat hair. This yarn is doubled and then folded in four and twisted to make a four-ply cord. The looped ends of the fourply cords are then slipped onto a wooden stick or spindle. An expert girth maker can use as many as sixty separate strands.

The basic structure of ply-splitting work is similar to plaiting in that the warp elements travel diagonally down the fabric from selvedge to selvedge. However, instead of passing over and under each other, one four-ply cord is untwisted sufficiently to allow another to be threaded through it. By varying the initial sequence in which the strands are attached and by choosing whether to thread one strand through another or have the other pass through it, it is possible to build up a range of patterns.

There are several basic pattern structures that can be formed using variations on this technique. The resulting girths can be monochrome (usually in black), have a black-and-white diagonally chequered pattern or alternately black-and-white horizontal waves. The most visually interesting structures, obtained with fourply yarn that is half white, half black, are geometric or figurative with the pattern appearing in negative on the reverse.

Uses

THE villagers of Western Rajasthan in India are particularly adept at making camel girths using this technique. Ply-split darning is a similar technique in which one strand is used as a weft and threaded through a set of warp elements. Ply-split textiles can be found in Egypt, Turkey, Greece, Nepal, India and Japan.

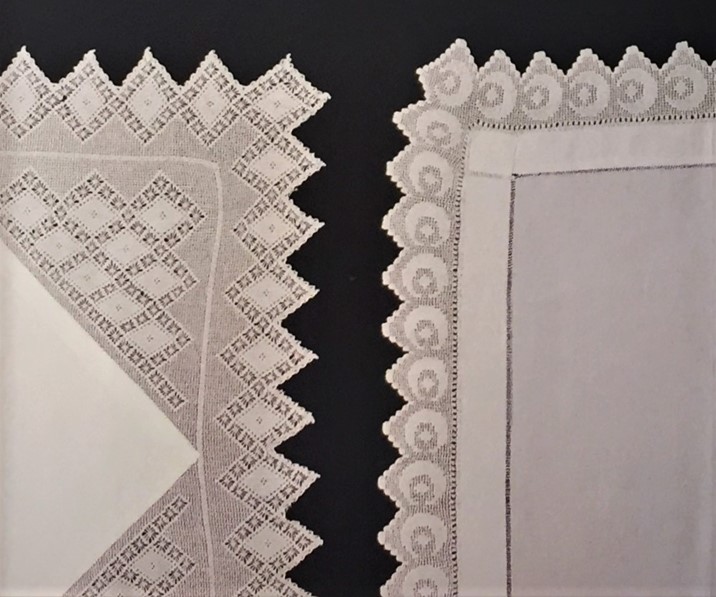

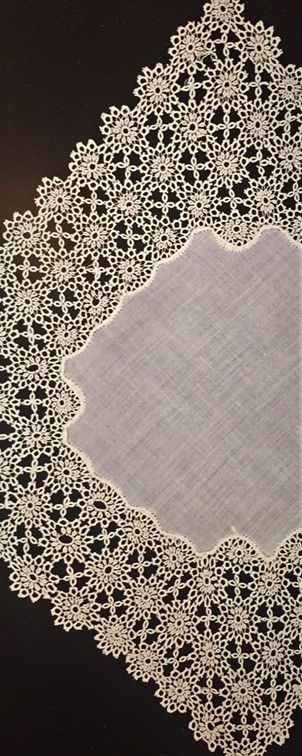

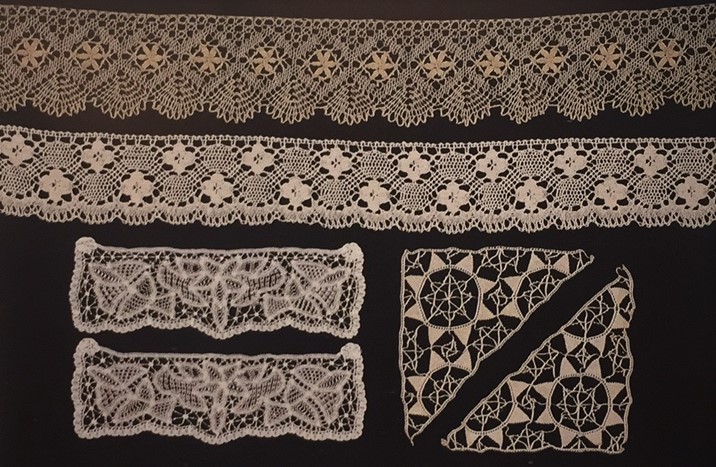

LACE

LACE is a European invention, made by the poorest of women to adorn the clothing of the rich. Probably the most recent traditional textile-making technique to come into existence, it seems to have originated in Italy or Dalmatia (the coastal region of the Former Yugoslavia) in the 15th century, but the technique and the fashion for its use spread rapidly to countries as far apart as England and Russia. It was later introduced to other parts of the world by Christian missionaries whose vestments were ornamented with lace cuffs and collars. Generally speaking, peasants are and were the lace makers in Eastern Europe, but in Western Europe lacemaking was a profession. Hand-made lace was always expensive, and the death-knell of the lacemaking industry in Western Europe was sounded in 1818 when the first bobbin net was machine-made in France. But in the conservative societies of Eastern Europe, peasant women continued to create bobbin lace to decorate their festival clothing. Tape lace was a specialty in Eastern Europe, especially in Russia.

Bobbin Lace

Bobbin (or pillow) lace is worked over firm pillow on to which a paper ‘G pattern has been fixed. Needles are inserted into the pattern to support the work and a number of threads, weighted by bobbins of wood or bone, are twisted and interlaced around them to create an open-work mesh. There are many regional’ styles, from that of the cottage industries ‘i of rural England to the sophistication of Brussels and the Mediterranean styles of the islands of Malta and Cyprus.

Needle Lace

ORE time consuming than bobbin lace, needle (or needlepoint) lace has always been more expensive. Using a needle, long chains of buttonhole stitches are worked which are looped and linked up as the work progresses to form net-like patterns. Once known as the Queen of Lace, complicated figurative patterns can be created with as many as one hundred stitches to the inch.

Tatting

TATTING is a form of lace-making worked with a small shuttle. Knots and loops or picots are worked on a ground thread which is drawn into rings or semi-circles and built up into delicate patterns.

TWINING AND WRAPPING

TIWINING and wrapping need some sort of frame for their construction, use a warp and a weft and greatly resemble loom-woven textiles. The warps and wefts are, however, manipulated by hand and, therefore, need no system of heddles to open a shed. The similarities to basket-making methods suggest that these techniques may have been in use over a much larger area of the world before the invention of the true loom. In places, twining and wrapping techniques are used in combination with loom weaving technique.

Weft twining

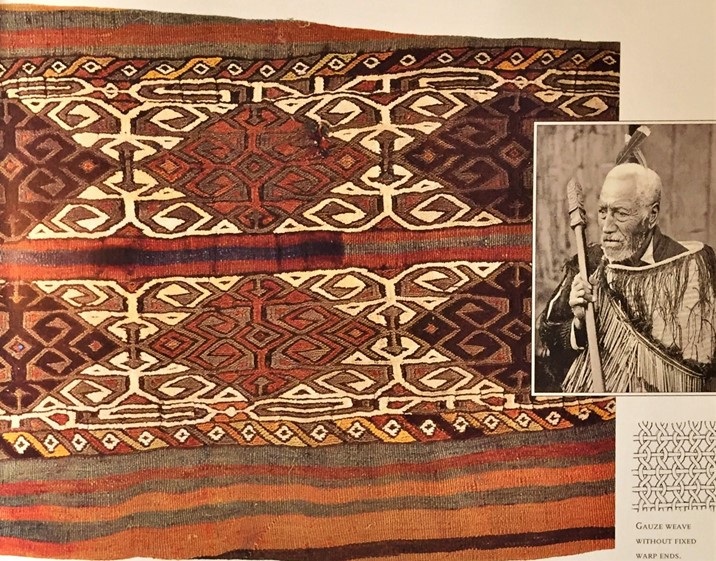

FOR the manufacture of a weft-twined textile a set of warps are suspended from a fixed rod. To maintain tension, weights are often attached to the bottom. The weft strands are then worked in pairs. One strand passes over a warp, the other under. The strands are then twisted around each other so that the first strand will pass under the next warp and the other over it. In this way, the weft twists and twines across the fabric from one selvedge to the other. The most amazing textiles woven using this method are the Chilkat blankets made of cedar-bark fibre by the indigenous people of the North West coast of Canada and Alaska, and the phormium fiber cloaks worn by the Maoris of New Zealand.

Warp twinning

Much as in weft twinning, it is possible to bind in the weft by twisting and twining the warp. This is an ideal technique for the constructions of long narrow bands. Warp-twined textiles can also be woven with tablets.

Weft wrapping

In this technique the weft threads do not merely pass over and under the warps, they are actually wrapped right around them. In the case of sumach technique popular in Balouchistan, Anatolia and the Caucasus, the weft wraps around several warps at a time. Fine, hard-wearing bags and rugs are woven in saumak, sometimes with the addition of a ground weft.

Gauze weaves

Gauze weaves, woven for centuries in China and South America, are very similar to warp-twined textiles except that the warps cross and are anchored by a pick of the weft and then uncross before the next pick. They do not twine around each other. Like sumac gauze is often incorporated into a loom-woven ground weave. A baf areas are woven.

KNITTING, is a technique where an interloped textile is created by horizontally manipulating a weft yarn with two or more needles. Traditionally wool is used, although sometimes cotton. The Egyptian Copts, a Christian sect who became famous for their skill, are credited with inventing the first true knitting. As Christianity spread, knitting spread with it, travelling as far as Peru with the Conquistadores in the 16th century. Although it originated in a hot climate, knitting is now most often practiced in temperate or cold countries and requires only an adequate supply of yarn. In Europe and Central Asia sheep or goat wool is used, but in the High Andes of Bolivia and Peru alpaca, llama or vicuna hair is more readily available and is knitted into beautifully soft garments. Plain, functional sweaters knitted with naturally oily wools are the choice of seafaring and fishing folk such as the inhabitants of Guernsey and the other Channel Islands.